What can a neophyte (Canmore resident for only five years) write that might qualify to be included in a “History Book”? Neither Alison nor I have roots or relatives in Canmore, but we have had contacts over the years – many years – with this delightful town and its people.

As a young teenager, I was one of several students given a priceless gift by a Calgary high school teacher – she introduced us to the simple joys of hiking in the mountains. At a time when many families, including my own, lived below the poverty line, a trip from the city to the mountains was a luxury far beyond our means. Miss Catherine Barclay invited us to go hostelling. We could ride our bikes to the mountains and stay in a Youth Hostel in Canmore for twenty-five cents a night.

Miss Barclay claimed that hiking in the mountains would do wonders for the growth, maturity and happiness of teenagers. Looking back across the passing years, I cannot today overestimate the lasting value of the gift she freely gave us. Thanks to her, our values and attitudes all took an upward turn.

Others have described the Canmore of the 1930’s as “a dirty little mining town” and that description accords with my memories. Houses in need of paint far outnumbered the fancy ones and the muddy streets in springtime were a challenge to vehicles, people and horses. The Youth Hostel was a rambling two-story building that once served as a hotel, owned by the Riva family, I believe. But it served admirably as a base for city kids learning the mountain trails. We were usually chaperoned by “leaders” and took our turn with chopping firewood, cooking and washing up piles of dishes, and general maintenance. In those days, we slept on “ticks”, gunny sacks sewn together and filled with straw. Comfort was often missing but few hikers complained.

In 1939, Miss Barclay introduced a bunch of us to the Twin Lakes (now known as Grassi Lakes), two gems of clear cerulean blue nestled in a deep ravine below Whiteman’s Pass and a fair hike up from Canmore. The sheer beauty and stillness of the lakes even inspired one of us to write a poem. But our beloved teacher insisted that our young eyes would not have appreciated the beauty, had we not had to hike all the way up there from the town.

I remember going with other hostellers from Calgary to visit Lawrence Grassi who lived in a small bungalow on Three Sisters Drive. During his lifetime, he selflessly gave endless hours and days to build mountain paths and trails so that Bow Valley dwellers might explore on foot and enjoy the scenery and natural beauties he loved so much. He was also known as a skilled guide and mountain climber and in 1925 made the first ascent of the “Middle” of the Three Sisters.

Strangers as well as friends were welcomed into his poky little living room, in fact squashed into it. A bachelor living on his own, he somehow rustled up enough drinking vessels of one kind or another so that all his guests got tea and something to go with it. Few people knew of his skill with a camera, but with the blinds drawn, we teenagers thrilled to see slides he had taken of wild flowers of the Bow Valley. He possessed an extraordinary appreciation of beauty. His creativity expressed itself in many ways. Alison and I received from Grassi intricate carvings made from elk antlers, including a beautiful cribbage board. He also presented us with walking sticks shaped from willow branches and bearing our initials.

In later years, our paths crossed again. Grassi was warden at Lake O’Hara when we camped on the meadows in 1961 with half a dozen kids. It was almost impossible to walk past his cabin without being invited in for tea. There are forty miles of excellent hiking trails in the O’Hara area, many or most of them built by Lawrence Grassi and Dr. W.K. Link from Pennsylvania. We saw some of the huge rock slabs that Grassi had lifted into place to bridge streams or gaps in the trail, witnesses to his legendary strength.

In 1971, we rejoiced to come across a plaque honouring Grassi on one of the O’Hara trails, placed there by the Alpine Club of Canada that had made him a life member. He died in 1980 but his name and reputation as a mountain-lover and builder of trails par excellence are perpetuated in Grassi Peak and Grassi Lakes.

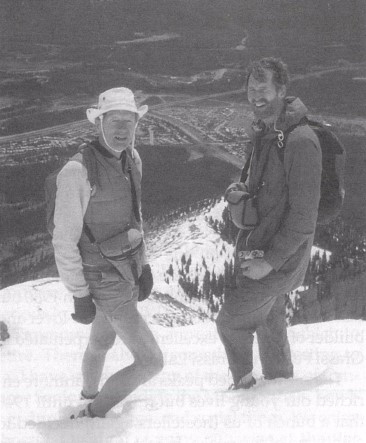

The snow-capped peaks around Canmore enriched our young lives but it was not until 1946 that a bunch of us (hostellers again) decided to climb one of the peaks. In fact it was one day in April when we had ridden our bikes (in stages) up from Calgary and stayed in the Hostel and slept on the same uncomfortable ticks as before. That Sunday morning we clumped into Ralph Connor Memorial Church wearing our heavy boots for the eleven o’clock service. Not until 1:00 in the afternoon did we set off to climb Mt. Lady Macdonald. The steep pitches didn’t seem to bother us then and five of us made it to the summit. I remember that the biting gale almost blew us off the summit ridge. When you’re young, nothing seems to bother you.

And when you’re old, you sometimes do foolish things. One day in February, 1996 (one year after we had moved to Canmore), the thought arose: “What about a repeat ascent of the peak fifty years later”? The idea just wouldn’t go away, and a few friends and family members said, “Why not”?

So on May 19, 1996, a party of thirteen set out to climb the mountain, about 4200′ in elevation above the starting point. Two-thirds of the way up, we stopped for lunch on a sort of plateau overlooking the broad Bow Valley. The wind was blowing a gale over the upper snow-covered slopes. Maybe that was a good time to quit.

When someone suggested “Let’s give it a try” , nothing more was needed. Five hardy hikers

braved wind and knee-level snow to slog their way up to the summit ridge. It was chilling and exhausting, but exhilarating beyond description. But there was no feeling of “conquering the mountain”; it was more like the mountain sharing with us some of its majesty and mystery. For me, the opportunity to scale the peak I had climbed as a young man fifty years earlier was a thrill making for one of those rare days that shine like beacons.

A few years ago I began to make a list of “Gems of my Life”, that included all manner of things, people, places and events that had enriched my life and for which I wished to thank God, the giver of all good gifts. The list that began with half a dozen items has grown to one hundred and fifty-five. I simply can’t go over any part of the long list without being overcome by feelings of thankfulness.

Hiking is not at the top, but it’s not far down. I’m still hiking, and although the hills still have their charm, they seem to be getting steeper and my rucksack heavier. But I don’t want to give up, at least not yet. I still delight in breathing the fragrant air of the pine forests, kneeling by a cluster of mauve moss campion blossoms, and marvelling at a shimmering green mountain lake or the silhouette of a mountain peak against the twilight sky.

Are we thankful to be living in Canmore? Absolutely, without any shadow of doubt. But not just for hiking. Canmore is a fine community of interesting, caring and creative people. I just hope it will stay that way.

HANKINS, Gerald

BETTER THAN SILVER OR GOLD

“Knock, knock.”

I knew it would happen, and it scared me half to death. For a second I thought about sneaking under the bed or making a dash for the front door. That knocking meant trouble for sure.

Sitting by the window trying to do my homework, I’d seen three tough-looking men sauntering towards our house. From the shoulder of the dirtiest one hung an open haversack and in it I could see something shiny and sharp.

“Knock! Knock!”

This time the back door was really getting thumped. Suddenly the whirring of my grandmas’s foot operated machine stopped dead. I just sat fiddling with my scribbler. Then I spied Grandma heading towards the knocking. She opened the door wide and stood on the sill, arms akimbo.

“Well, gentlemen,” she said. “What can I do for you?”

“We’re pretty hungry and tired, lady, and would sure like some food. We’ll do just about anything for a meal,” said the man with the haversack. From where I sat, he looked grey and worn-out. His two buddies had already flopped down on the back porch.

Grandma pursed her lips and looked down at the floor. Looking for inspiration, she drew her hand across her chin, just barely missing a dangling cigarette butt.

“I know about hard times,” she said with a nod. “But we’ve had a good garden and a neighbor gave us some beef. Let me see. You could split a few logs in the woodpile there and pull some weeds in the garden, for a start.”

The three tramps said nothing, as if trying to save their slender energy, and got to work.

I’d seen plenty of bums and tramps before this August day in 1931, although few of them ever got to our little village of Midnapore, just south of Calgary. They whizzed through on the freight trains —”riding the rods” — crowded together on the flatcars, clinging to the steel ladders, or clustered up on the roofs breathing smoke and soot. An empty boxcar was sheer luxury. Most of them didn’t know where they were travelling, but they sure knew why — looking for work, food, anything.

At the age of eight, I thought everybody was poor. And looking back on it, I wonder how they — or we, for that matter — managed to survive those bleak years.

For a while I listened to the whacks of the axeblade striking wood before getting up to stoke the old smoking, wood-burning stove. Then I trundled after Grandma down into the cool dark root cellar and helped her bring up potatoes and carrots.

Grandma was one of my favorite people. She didn’t exactly spoil us boys — she was just a great believer in “self-expression”. Oh, she could get after us alright, but a few seconds later all would be forgotten.

In my mind’s eye I can picture her today — sitting at the table rolling her own tobacco and later puffing away on some stringy, deformed cigarette that always seemed to be smoldering one inch from the corner of her mouth. She had a gentle and uncomplaining disposition in spite of almost unbearable hardships. Emigrating from England in the early 1900’s, she and Grandpa ran into repeated disasters — like grasshoppers eating up their crops. When three years of drought followed the grasshoppers, they auctioned off the farm in 1928 and moved to the village of Midnapore. The next year the Great Depression hit.

I can’t remember my Grandma ever grumbling about anything, but I do remember her often talking of the day “when my ship comes in.” I pictured then a great four-master, sails billowing in the breeze, swishing into port laden with jewels, silks and gold coins — all for Christine Towner.

“Anything I can do, Grandma?”

“Why, yes you can, dear. You can go out and get an armful of the wood they’ve cut. Then tell them to come inside in twenty minutes.”

This was the very job I didn’t want to do — to be honest, those seedy-looking tramps gave me the cold shivers. I wouldn’t have put anything past them. I shuffled around a bit and took as long as I could before slipping out into the yard.

All three of them were hard at work and had chucked their raggedy jackets down on the ground. One was splitting logs while his buddy was piling them up neatly. The other fellow was kneeling in the potato patch, picking weeds. I grabbed a quick armful of the firewood, told them when to come in, and hurried back.

All sorts of nice smells drifted through the kitchen door when I walked in. Two pots on the stove were steaming away merrily. Grandma had buttered some homemade bread and set it beside three plates warming on the stove’s reservoir. Then she opened the oven door and hauled out a piece of meat. Three glasses of milk were on the table.

Some time later we heard gentle taps on the door. Grandma opened it and invited her guests in.

“Thank you, ma’am, but we’d be quite happy to sit out here. I’m sure you’d like it better this way,” said one of them.

So the drifters sat down outside the back door. Grandma didn’t keep them waiting long. In each hand she carried a plate heaped up with steaming potatoes and carrots, roast beef and gravy, lettuce and home-made salad dressing. The third man got his heaping plate on the next trip. My job was to carry out the buttered bread and glasses of milk.

It didn’t take our three friends long to gulp down Grandma’s dinner. After all, they were starving. Their table manners weren’t the best, but that didn’t seem to bother Grandma: she actually sat down with them, a benign smile on her face.

“Anybody for seconds?” she asked, after the surface of each big dinner plate saw daylight again.

“Gee thanks, ma’am,” said one of the men, “but we really haven’t done so much to deserve all this. ” Still, he was willing to have another go-round of anything left. So were his pals. With a little fuel once again stoking their fires, color returned to pale cheeks and sunken eyes began to sparkle.

“I’m Jim from Guelph and I’d sure like to thank you. I’ve been riding the rods for two months and don’t have a cent,” one man said.

“And I come from Regina where I used to have a good job with an accounting firm,” said another who introduced himself as Francis. “There’s long line-ups at the soup-kitchens in Regina.”

The third fellow, Bard, looked like he hadn’t shaved or changed his shirt for a month. “I’d been to university for two years and had to quit when the money ran out. I left Vancouver a month ago and can’t get a job anywhere and gave up looking. But now,” he paused, “I might just try again.”

For a while they just sat there, talking about this and that, with Grandma listening and nodding and asking the odd question.

Then they got up to leave.

But just before going, each one of them took off his cap, extended a grubby hand to Grandma and thanked her, as only starving men who have been filled can do.

“We won’t forget, Mrs ….”

“Towner. Christine Towner,” said Grandma.

“Mrs. Towner, we won’t forget,” said Jim.

“Maybe some day we’ll come back wearing better clothes and thank you again. I’d say that all of us rate this the best meal we’ve ever had.”

So the three hoboes headed down the path to the tracks to catch the next freight train going anywhere.

That day taught me lessons they don’t teach in school or college. And I guess neither Grandma nor I ever thought we’d ever see any of our derelict friends again. Grandma died five years later from lung cancer, probably from a lifetime of smoking her roll-your-own cigarettes.

A few months after Grandma died, my mother moved to Calgary so that my brother and I could go to high school. Times slowly improved and we tended to forget the hardships at Midnapore but I never quite forgot the time Grandma fed the three starving tramps.

In January, 1942 I rode my bike down to the Air Force Recruiting Depot to join up. After I’d completed a lot of forms, a corporal took me into the examining room. “Just strip and lie down there and the medical officer will come and examine you,” he said.

I lay down under a sheet and in a few minutes the white-coated doctor showed up. A stocky middle-aged man with a black moustache, he shone his light in my mouth and ears, pummelled my tummy and listened to my chest.

Slipping off his stethoscope, he sat down at the desk and starting ticking off the boxes in the form.

“Any previous illness or bad accidents?”

“Nothing serious,” I said. “Oh, I did have a bad case of whooping cough when I was just about nine. “

“Were you living in Calgary then?”

“No. We lived in Midnapore,” I said.

“Really?” he said, putting down his pen. “Would you have been in Midnapore back in 1931 or ’32, by any chance?”

“Yes, I was there. But I was just a boy then.”

“You didn’t happen to live in a house near the railway tracks, did you?’

“We did. We lived there with my grandparents. Why do you ask?”

“Was your grandmother’s name Christine Towner by any chance?”

“It was.”

He got up, walked around the desk to the examining couch and shook my hand — shook it as if I were a long lost younger brother. For a while he did not speak. Then he pulled up a stool and sat down close to the couch where I lay under the sheet. With one hand on the couch and eyes lowered to the floor, he told me the whole story of the day in 1931 when my Grandma fed three hungry men. “I was one of those men. Today I’m known as Flight Lieutenant Bard Peterson, M.D. Do you remember that day?”

“Yes, I was with Grandma. One of you chopped firewood for her and she fed you out on the back porch.”

“Right, but it was no ordinary meal. I remember the big dinner plates chock-full of hot, homemade food. We hadn’t eaten for days. Your Grandma’s dinner meant far more than silver and gold to us.”

“It looks like you’ve come a long way since then,” I said.

‘That’s true. That good meal did wonders for us, in more ways than one. Sure, we got hungry again, but somehow never so desperate. It was almost like getting a new lease on life. All three of us eventually got odd jobs and finally settled down. I was lucky enough to get back to university and graduated two years ago.”

“It’s amazing,” I said.

“It is amazing. ” Then he cleared his throat and looked me straight in the eye.

“I can tell you now that things would have been different, had it not been for your Grandma. I was carrying a big hunting knife — we were all set to rob you.”

“But somehow I just didn’t have the heart to draw the knife on your Grandma.”

Gerald Hankins and son Paul on summit ridge of Mt. Lady Macdonald 1996

Lawrence Grassi at Lake O’Hara, 1961, with four children of Alison and Gerald Hankins

In Canmore Seniors at the Summit, ed. Canmore Seniors Association, 2000, p.114-119.