I was born on January 5, 1933, in Medicine Hat, Alberta, the only son of James Langus Turner (1910 – 1991), a contractor, and Mary Wilhelma Becker (1913 – 1941). They married in 1931. My mother died prematurely from tuberculosis on my birthday. It is presumed that her sister, a nurse named Katherine, brought the disease home infecting both Mary and Marjorie, another sister. Katherine and Mary died from tuberculosis. Marjorie did not.

In 1950 I apprenticed for five years in the piping trade, specifically steam fitting. I was certified as proficient on March 30, 1955. I was indentured by Haddow and Maughn of Edmonton and N. Turner & Son of Medicine Hat for the five year work and training period. I was initially employed during construction of the Cold Lake Airport (out of Edmonton) winding up with industrial, commercial and service work in Medicine Hat and surrounding area. I was at this time introduced to fly fishing by my father, passionate at this recreation whose motto was “Don’t get caught with your fly down”.

In 1954 I was married in Cold Lake. My children are Beverly, born in 1956; Leslie born in 1958, and Ross born in 1961. I have a total of nine grandchildren. I divorced in Calgary in 1973.

In 1960 I was employed by Hayhoe Plumbing and Heating Ltd. of Red Deer, Alberta. My job was supervisor of plumbing and piping installation including sub-trades in sheet metal, instrumentation, welding and piping insulators for a total of 70 men during peak construction of the two-story underground radiation fallout shelter built at Penhold, Alberta. There were six of these built across Canada, the largest in Ottawa, Ontario, with four stories all underground. It was a time of the East versus the West, the Cold War was at its peak and the scare was radiation poisoning from the atomic bomb. The intent of the buried shelter was to hold municipal, provincial and federal levels of government in the event of nuclear holocaust and to function as the nucleus of government if needed.

In 1962 I was hired by Trotter & Morton Ltd. of Calgary, Alberta, my employer for the next 18 years. In 1963 I obtained my 4th Class Power Plant Engineering certificate from SAIT night classes. In the same way I obtained my Math for Trades certificate. I joined the Hook and Tackle Club in Calgary to enhance fly-fishing techniques and learn to tie flies. I also became involved with stream improvement, field trips, club smokers and socials, club derbys and observed the philosophy of conservation and trout and stream enhancement. The club motto was “Better Fishermen for Better Fishing”. I retained membership for only a few years due to extensive travel for work.

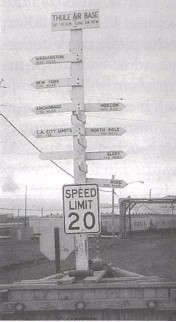

Greenland

1964 found me in Thule, Greenland. I installed the heating and piping system in a complex of ten prefabricated trailer units at Atco’s plant outside Airdrie, Alberta. I was an employee of Trotter and Morton who contracted work for Atco. Atco’s customer was the U.S. Airforce; the project was for Thule, Greenland. Greenland is Danish. Thule has no plant growth, just shale and rock. Inland from the shoreline for many kilometres the rock and shale does indeed transform for summer and winter but ultimately inland gives way to a sheer wall of ice and snow hundreds of feet in elevation. I have not concluded why the Greenland Icecap is called “green”.

There was something more sinister, however, than shale and rock and snow at Thule, Greenland – the network of trails leading away from the main base camp ending at a multitude of missile sites, all aimed for Mother Russia. The Cold War again. It required two separate trips to connect and commission the trailers as transport by ship required two separate voyages to the continent. Why? Because they shipped the wrong five first.

Alaska

1965 found me in Bornite, Alaska. Opening a map of Alaska will show a large bay identified as Kotzebue Sound. It is located right up in the north and west side of the U.S. state about as close as one could want to the Bering Strait where western Alaska and eastern Siberia almost touch. The Inuit settlement of Kotzebue was the jumping-off point from commercial airlines to bush plane in order to reach Bornite, Alaska. Seen from the air Kotzebue is a small but busy place during the short Arctic summer. Gazing from the aircraft window just prior to landing a huge mound of unidentified material could be observed some distance out on the sea ice. After landing a friendly and talkative sheriff’s deputy cleared the mystery by stating this was the local refuse tip. As summer advanced and the ice melted it soon disappeared. The deputy also offered a true event from last winter. While on duty at the local community hall for a weekend dance, and standing in the entry foyer, he heard the unmistakable sounds of intimacy from outside. Investigation did indeed reveal a couple in compromise in the Alaskan snow. The temperature outdoors was a stunning minus 40 degrees.

You will not locate Bornite on very many maps. The word identifies a specific composite of copper-bearing ore. As a geographic location, Bornite is simply a mine site for copper extraction in the middle of nowhere, Alaska. The prefabricated trailer modules by Atco were actually fabricated in 1964 but due to low water flows in the Kobuc River that year could not be barged upriver. The entire package overwintered at the mouth of the Kobuk where it discharges into Kotzebue Sound. I was pulled from a construction site in southwest Calgary at the end of May and flown to the mine site for a two-week stint connecting the mechanical portion of the contract package. The beginning of June turned into the end of August, a very long time to be in an alcohol-free camp for a connoisseur of fine Canadian Crown Royal. The money and a few afterwork pleasure trips made it all worthwhile. How often in life does one get the opportunity to catch six-pound trout while balanced on the pontoon of a float plane at a lake in the Alaskan wilderness at no out-of-pocket expense? Or for that matter actually hook and land a wild trout by dangling a fly inches above the surface of a 6-foot-deep gin-clear creek with one hand on the fly rod, the other snapping a photograph of the impending strike in bright sunlight at 1 A.M.? Atco’s customer for this project was Kennecot Copper of Utah, U.S.A.

1966 – South Pole Polar Plateau Antarctica Would you believe it if I declared it impossible to contract a common cold at the South Pole? It is indeed true. The extreme cold has created a sterile environment and this type of infection is not possible. Howeveras soon as one leaves the continent one will be infected; if only the sniffles, it will happen, possibly as early as the flight out. This Atco project of specialty trailers was prefabricated, test run, disassembled and shipped from Atco’s new production facility at Lincoln Park, Southwest Calgary. Atco’s customer was the U.S. Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks for use by a mix of scientists together under U.S.A.R.P.,United States Antarctic Research Program. Destination was 600 miles from the South Pole (geographic, not magnetic). The purpose was what else? Scientific studies such as the Aurora Borealis, wind elements, ice core samples, the effects of isolation among humans, etc.

Shipping of the trailer modules was by three modes of transport: rail, ship and air. My first contact with the trailers after initial installation and testing in Calgary was at Lyttelton harbor on the south island of New Zealand. Atco office’s instruction was for a final inspection before the journey to the Antarctic continent by ship. This trip was a little different in that although still an employee of Trotter and Morton Ltd. of Calgary, I was to represent Atco as their field supervisor. In plain English, the mechanical aspect was not where it started and ended for me this time but was only part of the entire picture, the field erection and finishing to customer acceptance of the Polar Plateau Station.

The Antarctic Continent has many keepers: the U.K., Argentina, Australia, U.S.S.R., Belgium, South Africa, New Zealand, France, and good old U.S. of A. International agreement by all involved nations has declared no military or threatening activity. Scientific exploration only – indeed Russia does winter over at U.S. bases and vice-versa. This is a major feat of personal tolerance when temperatures drop below minus 100 degrees F and there is no sun at all for months on end.

McMurdo Sound in Antarctica was late thawing in 1966 requiring “ice-breakers” to open the way through pack ice for unloading the ship’s cargo. Once off ship the individual components were dragged overland, actually snow and ice, to the local “airport” (loose description) facility. “Williams Field” is the official name for this air terminal to the outside or local regions which sits atop the Ross Ice Shelf not far from McMurdo base camp. The 25-foot-thick shelf makes a respectable runway during the short southern summer at least until sufficient warmth creates a very shallow puddle of melted ice. In any event this is of short duration and there is no other option except the ice as a landing strip. One at a time the separate units were flown aboard U.S. Navy Hercules military transport to the South Pole. The plane’s fuel tanks were refilled, then on to the Polar plateau to unload its singular cargo. The Plateau is 600 miles from the South Pole which is rather unique when you think about it: no matter which direction you head from the South Pole it can only be “north”.

Fuel carrying capacity of the Hercules aircraft does not allow a simple fly-in-and-out type of picture. The distances required to fly from the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole to the Polar Plateau and back again necessitated the stock piling of jet fuel at strategic destination points. Also, as may be readily understood, the new Plateau station could only be accessed by the plane carrying return fuel as part of the payload as well as the intended cargo – a trailer.

The insecurity of life itself is most transparent when as a lone passenger your sole company is thousands of gallons of high-octane jet fuel. At least that was my feeling trapped in this huge flying boxcar, gazing uneasily at huge aluminum tanks using up all the space around me usually occupied by seats or less volatile cargo.

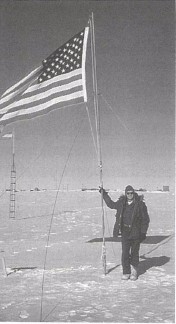

South Pole Station is a U.S. base but not what one would expect. There is indeed a pole, not created naturally or supernaturally, but planted in the snow by U.S. forces marking the exact geographic location for the bottom of the earth.

Accommodation and pertinent facility structures at South Pole station were originally placed atop the ice, actually packed snow, but incessant blizzards repeatedly buried everything, necessitating unending digging out. Eventually it was decided to go underground with connecting passage walls of ice and snow, the weight overhead supported by large steel “I” beams. Frozen food produce now had unlimited freezer capacity with the connecting passageways retaining a constant -20 degrees F, no matter what the temperature on top of the ice.

The outside area, viewed from outside or topside, is identified by a number of short hooded stove pipes poking through the snow like so many ship’s stacks on the horizon. A trail of smoke-like vapor rises from each whenever the heating comes on. No different than looking out your window in Canmore in winter and knowing when your neighbor’s furnace is running. Other than small weather balloon release stations the vent pipes are the only visible protusions in the vast expanse of white on contrasting incredibly blue sky. Access to underground is accomplished by tunnels angling up to the surface. After a blizzard it was a simple matter to excavate the tunnel entrance again.

A memorable experience was eating in the galley (military jargon for diner) with at least three dozen pots, pans or buckets scattered about on the tables and floor catching water dripping from the ceiling. The considerable weight of the packed snow along with the heat loss from inhabited structures underground had created unexpected problems when roof punctures occurred.

Loud pinging of water dripping into near empty metal-ware exacerbated the surreal atmosphere of living underground in remote surroundings. A stay of ten days was planned for the Pole in order to acclimatize to high altitude. The 2912- meter elevation was intended to condition one’s body to function adequately for work at Plateau Station which has air at even less oxygen content at 3624 meters (11 900 feet).

Christmas was celebrated at the South Pole. Actually not celebrated. There were no party hats, noise makers or liquid stimulants seven days later to wish the New Year in at Plateau Station either.

There was, however, a tent, that’s correct, a canvas tent, complete with food, a 2-burner gas Coleman camp stove, a cook, a scientist, and a reporter. The arrival of our flight was the first of many to deposit men, machinery, tools, equipment, and structures to assemble this remote scientific studies station. Construction branch personnel of the Navy are called seebees. Our forces consisted of perhaps a dozen seebees including, by chain of command, Captain Don Pope (army) on special assignment, Lieutenant Dave Ramsey, the chief, and lastly the bees (I guess). It was three days without sleep to erect a temporary quonset hut living quarters in order to place a bed for sleeping. Restroom facilities were very, very basic. A short walk from our living and working area were two upright poles pushed into the snow about 2.5 meters apart, a horizontal rod, chest high, and a shallow dished excavation in the snow surface. No walls, roof, door, vanity screen or any separation from natural surroundings – basic!

Aircraft unloading, placement and connecting of trailer components to effect a finished engineered complex went rather smoothly except for a few highlights worth mentioning. A $20,000 aluminum off-loading ramp, custom built for this project, had not been test run and the trailer undercarriage became jammed on the aluminum side rails on the first attempt to unload. It was easy to see what was required to solve the problem which I promptly relayed to the crew. That really helped. All work ceased. Instruction must proceed through the chain of command from Atco supervisor to Captain Pope to Lieutenant Ramsey to the Chief and he to the men. It’s smooth now.

Another more distasteful event arrived in the form of the naval commander in charge of Antarctic activities who had travelled all the way from Christchurch, New Zealand. As a direct result of the offloading incident and a no physical or “hands off” involvement for myself, a miscellaneous scientist had contacted the commander in New Zealand to complain “He’s not doing his job”, unaware, of course, manual involvement had already been disallowed for me personally.

The next recollection I perceive of this unpleasantry is the commander shouting “Do I know the reason I am here?” and I replying loudly “Who the H- do you think you are jumping on my back”. You get the drift. All this outside, temperature of minus 20 degrees F. 600 miles from the South Pole on 3600 meters of ice and snow. Very emotional and serious then, amusing now. Months later, after returning home in April local mail in Calgary delivered an envelope containing a medal and citation commending my contribution and the success of “Navy’s investigations in the Antarctic, etc.” from Rear Admiral A.C. Husband.

The station had a planned life of one year but in fact functioned for several. Life was solely dependent on the reliability of both the dwelling and its occupants with good design and pre-planning a major feature. There would be no flights in or out for at least 7 or 8 months of the southern winter which was endured in total darkness. The extreme low temperatures turned liquid jet fuel to gel. Consequently even emergency flights were not an option during those months. The midsummer high temperature reading in 1966 was minus 20 degrees F and continued dropping one degree everyday I was there. Even at that temperature all incoming flights with our equipment did not shut down engines to unload.

The camp logically was self-contained, three diesel generators, two operational and one standby, providing electrical power with engine cooling piped to allow snow melting for water provision, as well as heating stored diesel fuel. Fuel storage was outside connected by insulated aluminum piping (aluminum does not transfer cold) to an inflatable rubber (probably neoprene) bladder. The extremely large bladder was completely covered by an insulating blanket. Later information indicated the diesel generators did fail, a result of operation at high altitude and were replaced by redesigned and modified equipment. The seven designated scientists and/or specialists staying over winter had each been trained with an overlapping profession in the event of one them was incapacitated. The doctor had a rudimentary knowledge of mechanics, a geologic scientist with electrical, etc. etc. Fire is the most serious threat with nowhere to shelter if burned out. Provision for emergency accommodation was located not far from the main station which included minimum survival equipment – a diesel generator. Rope connected the two destinations for guiding yourself in darkness if it became necessary. The lowest recorded temperature for the region was minus 121 degrees F. You wouldn’t last long exposed to that cold. Shortly before project completion, the communications expert set up equipment to contact USA. by shortwave radio to allow anyone wishing to speak to family to do so. A public speaker for incoming conversation permitted all of us gathered to hear one side of the affair. None of the group had family within direct contact distance so it was necessary to relay through a telephone operator. The first operator contacted happened to be located on the eastern seaboard of the United States and when asked where is this call coming from, our reply was the “South Pole”. She of course reiterated “Sure, it is. Now where are you really calling from?” But of course it was, or at least close enough. Upon the return trip and of course travelling back through South Pole Station I learned the resident cook had gone berserk and shredded special recipes formulated for the climate. It was my understanding he was flown out in a straight jacket. We must be thankful the cook’s expertise did not lend itself to piloting skills. On the other hand maybe the incessant pinging took its toll.

1967 Gillam, Manitoba

There was no overland summer highway, gravelled or otherwise, connecting Gillam, Manitoba, to the rest of Canada in 1967. There was, however, landing for flight by air and an all-season rail line. Gillam was the staging area for supplying the accommodation, feeding and business needs of personnel constructing the giant Kettle River Rapids Hydro Dam. The town located very near the Nelson River is one of many aboriginal settlements scattered throughout the north country.

It was several hundred kilometers south of Churchill, on Hudson Bay, which is closer to the border of the Northwest Territories than Gillam. Churchill occasionally makes news because of the polar bears and polar bear problems. Our contract with Atco was more commercial than residential bunk trailers this time around. We supplied, shipped and installed steam boilers and related piping, including mechanical equipment to facilitate a large mess hall, all components prefabbed in Calgary, where feasible. Work got off to a good start when it was discovered our supplier in Calgary had shipped by rail an entire flatbed of large bore steel piping of incorrect size. Dozens of twenty foot lengths constituting thousands of pounds were returned and replaced with that originally ordered. Very costly error to be sure, but not for the contractor. At the very least we caught the mistake before the railcar was unloaded.

The bulk of manpower working on the hydro dam and related support services was flown in from Winnipeg. It was inevitable a shyster or two made up the mix. One particularly inconspicuous con-man had worked, eaten and co-habited with us for several weeks, blending in and establishing some trust. He was blond, blue-eyed, softspoken and quite simply looked and acted like everyone else. About ten days before the ‘Icon”, he let it be known and did write up purchase orders for anyone wishing to choose items from a catalog he presented. Under no condition would he accept any prepayment until the product was in our hands. Then you must pay. Sound good? It wasn’t. On the morning of the day the goods were to arrive, he began pestering everyone who had ordered for either a down payment or payment in full. Those who had not purchased were pressed for small loans. Anything. $5. $10, whatever you could, to help him pay for the delivery. The plane that should have delivered the goods did not. The out-going flight that day did seat our con-artist back to Winnipeg. I did not hear what the dollar value of the swindle amounted to, or whether he was ever apprehended. A search of his sleeping room the following day disclosed an old empty suitcase and a set of shabby clothes in the closet, purposely left to give the impression he was still around.

Anyone having wintered in northern Manitoba will be familiar with the January thaw. An annual occurrence when -35 degrees in mid-winter warms to near freezing for one or two weeks before returning to frigid winter temperatures. The phenomenon was extended for us that year in 1967 when Atco’s field office trailer burned to the ground (snow), a week before we wrapped up our work and left. The office trailer was existing on site when we arrived and was not a part of our contract.

1968 Williams Field Ross Ice Shelf Antarctica

Regardless where homo sapiens reside, visit, or otherwise may stop, “head” facilities have been and always will be a necessary fact of our life. To the unfamiliar, “head” is military for “john”, biffy, or just plain restroom. The facilities at Williams Field on the 25′ thick Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica had been lost to fire. The contract was an upgraded “package” for the loss. The trip, although I was not involved in the construction and prefabrication process at the Atco plant in Calgary, was to represent Atco and supervise on-site field erection to customer acceptance. The “package” as in earlier projects consisted of a series of trailer units or modules drawn together with electrical, heating and, in this case, plumbing interconnected forming a completed stand-alone complex.

Reluctance ran amok in my thoughts prior to leaving New Zealand for the continent, when our flight cued three times for boarding. Three times we were delayed due to unspecified mechanical malfunctions. Less than an hour into the air, after ultimately leaving, the entire passenger area filled with smoke. Inquiry response identified inplane heating system problems and “there was nothing to worry about”. Maybe not but the mere fact it was a military craft and not a commercial airline somewhat added to the uneasiness.

Again safety from fire, plus fire suppression, was a dominant theme throughout the design and building of the trailers. An elaborate system of C02 flooding from rows of standing cylinders piped to release heads was intended to deprive a fire of any oxygen, snuffing it out. A successful test firing was initiated as proof of functioning for final wrap-up after all else had been completed.

Waiting for the flight back to New Zealand was entertaining back at McMurdo station taking in some of the unique sights. Seals moving about on the broken jumbled sea ice. More seals sunning on the unbroken ice, having surfaced from a vent from ocean to topside. Scattered around like so many overgrown sausages, they had no fear of man, but could be approached and touched. A bust of Admiral Byrd was on prominent display outside, near the diffusion of base buildings in McMurdo.

Antarctic explorer Scott’s visit is more tangible by observing his base camp not far from McMurdo Camp. A wooden structure preserved as he left it before losing his life to the cold has been declared off limits and remains as a heritage site.

On the eve of continent departure at McMurdo I was pressured into a poker game with some visiting military navy brass at the local one and only watering hole. Gambling is not one of my passions. I do know how to play, I simply do not have the interest. This was different. Although somewhat removed, these people could be conceived to be Atco’s customers. So I sat in and played most of the evening, winning almost every hand. Later I was politely advised on the impropriety of being successful at cards with high ranking officers. How do you lose when dealt all the cards? Motto outside the drinking lounge where we played read, “We laugh because we must not cry”. Standing on wet ice the next day before leaving from Williams Field, thin wispy smoke could be seen rising from an active distant volcano. As I boarded the aircraft, suitcase in hand, a group of penguins in total disarray auditioned their stiff legged waddle dressed in black coat and tails. A runny nose was in progress before landing in New Zealand.

1969 Northern Saskatchewan

This trip ranks as the shortest of several. Five days on site. The pattern was the same though. Prefabricated in Calgary then shipped to the far north of central Saskatchewan where frozen muskeg allows overland access only in the winter. Discovery of uranium in the vicinity by a young geologist some years earlier was responsible for the choice of this particular site. Outdoor temperatures were approaching minus 60 degrees the first day on the job. By the time we left a few days later it had warmed to a paltry -10degrees F. Almost like summer in comparison. The memorable part of the whole exercise was leaving. The small

ski-equipped bush plane was limited in respect to payload for take-off and flying. On the planned day of departure it was requested to add additional baggage to the flight. A fourth passenger. This gentleman was of substantial proportions, easily 225 pounds. The aircraft’s carrying capacity was already stretched with the pilot, my apprentice helper, myself, and a very heavy steel box with plumbing tools. The pilot chose to give it a try anyway, to save an extra trip. It seemed to take forever bouncing across the frozen surface of a lake invisible under the snow. Eventually we did become airborne, but not by much. Meanwhile the huge pine trees ringing the shore were threateningly close in my opinion. At the last moment so it seemed, the pilot banked and returned to unload the excess weight. Our very plump passenger. Too much weight said the pilot. Yes indeed, said I wiping the perspiration from a permanently etched forehead.

1972 Western Centre Calgary

For the unfamiliar the plumbing trade can be as confusing as assembling a jet engine. That is, of course, if the extensive code book is adhered to. Like any other field of endeavour, be it professional or nonprofessional, it is all in the training and repetition. Erroneously the general public believes plumbing drainage consists of a pipe or pipes running down hill and that’s pretty much it. Not true. Without exception all plumbing drainage or sewer lines consist of two basic elements, or principles if you like. One is indeed the pitch or downward grade to allow gravity flow. But without the addition of air or atmospheric air pressure there would be no movement.Try drinking water from a hiker’s bottle or pouring milk from a narrow necked jug without allowing air to enter for fluid displacement. It’s the same principle for plumbing drainage.

In the early years of 1970 a consortium of copper producers and manufacturers introduced a new concept for high rise apartment buildings. It was called the “sovent” system. Advantages over a conventional system were mostly in the theme of monetary savings resulting from less materials, consequently less labor. Utilizing only copper and brass as base materials the copper industries’ interest and promotion is evident. Basically the concept was a special brass fitting incorporating oversized connections feeding local fixtures and not requiring an elaborate vent (air) piping arrangement as per existing code. The forty-two storey Western Centre building on the corner of 4th Street and Fourth Avenue in downtown S.W. Calgary was the first in western Canada to incorporate the Sovent System. The only other Canadian venture was in Ontario. As the mechanical superintendent on site, I was involved with this installation for almost 12 months of 1972.

1975 Mayo, Yukon Territory

Mayo sits in the north central part of the Yukon and is more or less the hub of mineral extraction, forestry, prospecting, and trapping for the upper half of the territory. Atco was contracted to supply and install a number of prefabricated structures to form a new school. My employer Trotter and Morton Ltd. of Calgary was a part of that contract. The plumbing and heating by our forces ran onsite from October and well into December. As outside contractors working in the north country, life revolves around rather fundamental certainties. Work long hours, three meals a day, the local watering hole for limited after work relaxation, and most important of all, surviving next to your fellow workers in close living quarters without succumbing to the greater urge to throttle each other over petty grievances.

Living and sleeping quarters were adequate, consisting of trailers rented from the business owners of summer employees no longer on site. Contents of bedside and other storage drawers revealed dozens of insect spray repellant cans, the only feasible protection against the warm weather onslaught of gnats, biting flies and no see-ums.

Midway through the work project, Remembrance Day to be specific, onsite Atco management deemed it worthwhile to fund a trip from Mayo to Whitehorse and back to rejuvenate the body and mind from the stress of working ten hour days, seven days a week. The passenger van was filled to capacity for the long drive south. Whitehorse had the atmosphere of a frontier town with numerous goldsmith shops where custom made gold jewellery was heated and shaped while you waited. Every bar and drinking establishment overflowed with patrons particularly on this long weekend. The hum, drone and horn honking of any progressive city. Most, if not all inhabitants of our far north, are independent, tough and strong. Whitehorse was no different.

On the third and last day of our holiday weekend we were waiting to be picked up from the agreed location in a parking lot adjoining a local hotel. The building had a small side entry door, visible from where we waited, and protruding overhead well out from the building was a substantial flat concrete canopy. As we watched in amazement a green half ton truck with a homemade camper in the back proceeded at very slow speed to drive past the doorway and under the overhang. It could not. In slow motion the concrete canopy decapitated the camper shell and deposited it in the roadway directly behind the still moving vehicle. The driver, almost in tears, declared he had completed it only last week and his wife was going to kill him.

Wrapping up and commissioning of the project in Mayo took an unexpected turn for the worse when all control manuals, brochures and design catalogs necessary to complete work in the finishing stages wound up missing. Everything in the way of printed instruction for operational settings that was integral to fine tuning were nowhere to be found. Without this information completion was simply not possible. Although not unheard of, it is very unusual to find animosity or uncooperativeness in construction due mainly to the overlapping nature of the various trades involved.

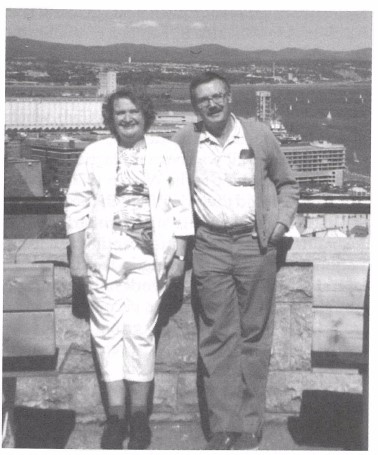

1979 Canmore

I married Barbara M. Hallewell who was born in Montreal But was more recently of Calgary. We moved to Canmore and with the help of Trotter and Morton Ltd. of Calgary, opened a mechanical contracting and service business in the name of Westbow Plumbing and Heating Ltd. Westbow was successful in the competitive bidding process as prime subcontractor for the Tourist Information Centre, the RCMP building and many other projects too numerous to mention. The 1988 Winter Olympic events held in Canmore were another contributing factor in the business success of the company. Westbow was in viable operation as a small business for fourteen years with myself as proprietor, and wife, Barbara, in charge of secretarial and book keeping duties.

1993

Retirement at age 60 was welcomed without reservation after 43 years. Westbow shares and stock were sold to new, younger ownership and management. On Jan. 15, 1996, a newspaper publishing declared Westbow Plumbing and Heating Ltd. was in bankruptcy.

As of 1993 and up to the present, retirement includes pursuing wild and planted trout from early April to mid October. A small selection of prized fly rods have whipped considerable water from the east Kootenays of British Columbia through Alberta and into the Cypress Hills of Saskatchewan. Tying flies fills the winter void until “Ice out”. Health permitting, the pursuit shall continue.

Jim Turner at the geographical South Pole Dec. 1965

Barbara and Jim Turner in Quebec City, 1994

International road sign in downtown Thule, Greenland

In Canmore Seniors at the Summit, ed. Canmore Seniors Association, 2000, p. 290-297.