The Ferguson Family Coat of Arms displays a flowering thistle with a bee extracting nectar together with the words in Latin, “Dulcius ex Asperis,” which might be translated as “Sweetness from Adversity.”

My dad was orphaned at age two in 1887 due to a typhoid epidemic when his parents were pioneering in the Northwest Territories near what is now Yorkton, Sask., and, together with an older brother and sister, was raised by an uncle on a farm in southern Manitoba. At age sixteen he attracted the notice of a railway agent who hired him as an assistant, and taught him Morse code. Soon he became a Morse operator. In 1914, he joined the Canadian Army and spent the next four years in France in the Corps of Engineers, First Canadian Division, as an operator.

A buddy, Jack Jones, was in the British army and had been assigned to the Canadians as a replacement after Canadian troop losses at the battle of Ypres. He had been gassed and was quite frail, so Dad took him ‘under his wing’ so to speak, which likely saved his life, for existence in the trenches wasn’t very easy back then. Jack took Dad home to Wales on a leave, and that is how he met Jack’s sister, Margaret. Dad persuaded the whole family into emigrating to Canada in 1919. Bert and Margaret were married at a Methodist church in Winnipeg, (St. Stephen’s) by none other than the Rev. W. C. Gordon, (pen name Ralph Connor) whose career as a minister started in Canmore some years earlier.

My parents soon moved to the USA where Dad hired on with the Milwaukee Railroad as an operator, expecting quick advancement to an agency. My sister, Winnifred, was born in Winnipeg, and I in Avery, Idaho, in 1926. The Great Depression dashed Dad’s hopes of steady work and we returned to Winnipeg in 1930, where he worked as a hired hand on farms until 1937 when he at last was able to find work as a relief operator in Calgary with the CN Telegraphs.

We were poor in those days, but never lacked for food. Dad was too proud to “go on relief.” Once he had to pawn his typewriter and violin, but when relief work was available with CN Telegraphs each summer, was able to redeem them, pay the landlord and grocery bills before being laid off again until the next spring, when it would start all over. This ended in 1939 with the declaration of war. Suddenly there was work again for everyone. Dad had steady work at the age of fifty five, not long to plan for retirement.

In 1944 I was drafted, after completing grade eleven at Western Canada High in Calgary. Dad had taught both my sister and me Morse code. He felt that one could always find work as an operator. The army assigned me to the RCCS, sending me to Kingston for training in the signal corps. The war ended in 1945. For me the month was October, because that was when the army decided I was no longer needed, and could return to civilian life and resume my schooling. The winter of ’45-’46 saw me struggling to cram grade twelve into my brain in six months. It was only a partial success. I passed enough subjects to graduate, but did not even write Chemistry and French as I was sure to fail them.

I decided to try for employment with the railway as an operator. My dad visited the CPR’s chief train dispatcher who gave me a Morse test, which I passed. He said he would call me when something came up. They took me on in June of 1946 but my first job was working for the dining car department as a waiter. Having already learned much of this sort of reasoning from the Army, I calmly accepted my fate.

My first assignment was making sandwiches in the basement of the old CPR station, then, a week later, as fourth cook on a dining car running from Calgary to Penticton and return each week. I hated this hot eighteen-hour workshift each day almost as much as making sandwiches. Finally, in September, someone remembered that I knew Morse code so I was sent to see the chief train dispatcher, Ernie Ketchum, and received my first assignment as spare assistant agent. I was sent to Didsbury, worked a shift under the agent there, then to Innisfail, and promptly caught measles (red), from a friendly puppy at the boarding house where I was staying. (He loved me by repeatedly licking my face at every opportunity). I went home to Calgary to my parents and was quarantined for two weeks.

In the fall of 1946, at the age of twenty-one, I asked my dad if I could join the Masons. I so respected him that I felt that I might emulate him by joining that ancient fraternity. I never regretted that decision, and joined Renfrew Lodge No 34. G.R.A. I wasn’t active in Masonry due to my nomadic lifestyle on the railway until 1956 when I was living in Milo, AB, as station agent there. I would demit from the old Lodge and affiliate with the new each time we moved.

After a succession of moves lasting a few days to a week here and there in Alberta, I was finally placed as night assistant at Coleman, AB, in the Crowsnest Pass. Coleman station was the dirtiest place I have ever worked, being downwind from the coke ovens, which poured soot, dust and smoke over the station twenty-four hours a day. I worked 10 PM to 6 AM unloading express shipments from Trains 11 and 12. This usually came to six or seven platform truckloads each shift, consisting of everything from sides of beef, groceries and perishable goods to drums of oil and machinery parts. The train crew helped with unloading but I was responsible for moving it into the heated sheds, then sorting and checking for shortages, and writing up the ‘waybills’ for the drayman, in the morning, to deliver to the stores. There were three coal stoves I had to stoke in the drafty old place to keep the goods from freezing. Knowing little of such devices, I shook them down well and, shortly, became so dirty myself, that after a shift, I was often asked which mine I worked in, International or McGilveray. I will never forget the time I left fifty pounds of butter too close to a stove and ended up with fifty pounds of grease to clean from the floor (money for which was deducted from my next cheque).

After a winter of this, I finally visited my boss, Mr. Ketchum, and reminded him that I knew Morse code. He looked surprised, then gave me a copy of the Uniform Code of Operating Rules and told me to return in a week for an exam in the “C Book” which would raise my designation from assistant agent to that of “operator”. I passed this test May 30th, 1947 (which date became my official “seniority date” as an operator). I was then sent to Morley for training under operator Don Swain. I sat at the desk and listened to the dispatcher working on the phone for a couple of hours. A message from the “chief” was sent to us by Morse that I was to board the “stock train” for Stephen to work the night shift (midnight to 8 AM). The regular operator had not turned up from days off and the 4 to midnight man was ill and needed relief. I jumped off the caboose at Stephen at midnight. Paul Collier was very happy to see me but was too sick to give me any advice. He jumped on the caboose and the train slowly moved a mile down the “yard” where he detrained at the operator’s shack and went to bed.

My first shift was a nightmare. Long freight trains arrived from east and west, “pusher” engines were detached, and engineers would come in for orders to return to Field or Lake Louise. The light in the train order signal was out and they told me it must be fixed. There was no electricity there in those days so I had to climb a forty-foot ladder to the light, remove it, climb down and refill the lamp with coal oil, light it, and return it to its place in the dark. By the time I had mastered my terror of the height and finished, I was cold, hungry and exhausted.

My last meal had been breakfast the previous morning. I sure was glad to see 8 AM arrive, but was immediately roared at by the day dispatcher for not “copying and repeating back the morning line-up”. I had no idea what he was talking about. The day operator came to my rescue, explaining to the dispatcher, A.W. La France, that I was “a green man”, then he copied it for me, repeating it back to the dispatcher. This line-up is issued each morning over the dispatcher’s phone for all the section forces on the entire sub so they will know where all the trains are. It is extremely important to them. Don gave me some breakfast and I tottered down the mile long “yard” and crashed into bed. I slept all day. That night the regular operator, Glen Troyer, was back and I was free to return to Calgary for a new assignment. I returned in style on Train 2 in the morning, getting a sandwich or two from the news agent.

My next assignment was to Rocky Mtn. House for a week. At “Rocky” I met Walter Bakka, the assistant agent, who taught me much needed information: how to make up a switch list for a train crew from the yard check book, how to look up a fare for a ticket to West Summerland, B.C., and how to bill carloads of grain and lumber. In turn, he was shocked to think a guy as dumb as me was already an operator.

After working at Rocky, I got what I considered to be a good position as operator on a work train on the Laggan Sub for the rest of the summer. It meant long hours. Twelve to fourteen hours a day, (big pay cheques) light work, supplying orders for only the one train, lots of time for fooling around with the crew, and I learned much about the requirements of the “Uniform Code of Operating Rules” which is the Bible all rail workers must abide by.

Often there were so many trains passing we didn’t get any worktime all day. Other times with slack traffic, they would work longer stints and I would have it easy. I could take a hike, go fishing or even have a nap, so it was really a great life. The gang was supplied with a cook, in a dining car, and it was then that I began to fill out. At the age of twenty-one, I lost my slim 26-inch waist forever. Breakfast always included oatmeal, dry cereal, bacon, ham, fried eggs, toast, jam, and lots of coffee, milk and juice. Lunch was usually sandwiches on the run, but supper nearly always included either pork chops or steak, if not a roast, and for dessert, canned fruit or CPR strawberries (prunes).

On Saturdays each week, the entire crew would “tie up” at some point, where there was someone to look after the engine, and ride a passenger train to Calgary for a day off. When they were close to Calgary or other large center, we ran “Caboose Hop” to Calgary’s Alyth Yard, and back out Monday early to be at the work site by 8 AM. That way I could get home for a change of clothes and a short rest with my folks before the next week. It was more likely that they would send an engine watchman out to where we were working and thus we nearly always rode in on a passenger train.

During that summer I lived in nearly every siding between Calgary and Field. At stations, where there was an operator, I really had it easy, as all my work was channeled from the dispatcher to the operator at that station. I would keep a low profile.

That fall I was taken off this job and waited for another posting. None coming, I bid on the only open vacancy in Alberta, that of “tramp” swing operator. Each week I worked three shifts at Aldersyde, and three at Burmis. Those were the days of a six-day workweek. The Burmis Lumber Company allowed me to buy meals from their cookhouse when they fed their men. I had three days off, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, leaving for Aldersyde at 6PM for the next week’s work. Each week during this time, and indeed until I finally married, I would return to my parent’s home in Calgary for rest and relaxation, and to visit my Calgary friends.

I did this for almost two years, and couldn’t return to the spare board without resigning and

losing my seniority – they had me over a barrel. Looking back on it, I was stupid, but I remembered the seven years my dad was unemployed in the Depression and considered myself fortunate to have a steady income even if I had no life of my own. Finally, in 1949, I bid in third operator Morley and escaped that awful swing.

Later, I bid on the Banff-Lake Louise Swing and was successful. No one else wanted it as it required an operator who knew Morse. I felt at last that I was beginning to have a life worth living. I still returned to Calgary every “three days off” per week, and slept in a boarding car set on a pair of rails off the track at the east end of Banff yard. While at Lake Louise, there was a boarding car for our use on “track 4”, opposite the station, not too safe a location as cars were often set off there. In fact one night, while a few flat cars were in this track coupled to the boarding car, and a snowplow was anchored on the east end, a pusher engineer decided to park in the West End of the track by backing in. Not seeing the flatcars in the dark, and not having a brakeman with him to “ride the point” and guide him safely, he crashed into the flats which rammed the boarding car. The result was a flat car slicing right through our “home”, demolishing it completely. Fortunately no one was in it at the time.

After about nine months at Lake Louise, I bid in second trick at Banff, 4 to midnight, when Walter Richmond retired. In Banff, at first I shared a basement suite with Cecil Walker, the third operator. It wasn’t long before I tired of this and found a suite at 404 Squirrel Street, in a house owned by a Mrs. Musson. She had two suites, or rooms upstairs, and several rooms, or cabins in the backyard that were rented out to tourists. She hired me to paint them at times, and Mr. Musson hired me to help tear down an old “Bankhead” house he had bought on Banff Avenue (east). He wanted to save all the lumber, but it was old and split easily, a very time consuming work which was finally abandoned in favor of demolition.

Banff station was a very busy and exciting place to be. As a train stopped, all passengers would alight to get coffee, buy souvenirs, cigarettes, or just view the area. The platform was a sea of humanity going everywhere imaginable. Twenty minutes later, the stationmaster rang a big electric bell and there would be a stampede by all wishing to entrain again. This was repeated again and again as each new train stopped. Even when no trains were due, we were busy, and always there were the telegraph relays clicking away in the background, communicating with other places, near and far. Morale was high, and the railway was a great place to work.

It was about that time that we all went on strike for about ten days and brought in the five day workweek that has expanded as the norm and is enjoyed by everyone to this day. In 1949 I began to dream of buying a car. Several other operators were like-minded. We decided that the best way was to pay for one in Calgary, but pick it up at the factory, thus saving the freight. They dreamed up the plan but faltered at the last minute. I went through with it and found myself owning a new 1950 Chevy hatchback but would have to get it in Oshawa, Ontario. I had never driven a car any great distance so I persuaded my friends to take the trip with me and teach me to drive on the way home.

In the spring of 1951, I met Ken Clark, a new operator who had worked on the CN in Ontario. He told me of rescuing a child by using artificial resuscitation. He didn’t have the skill, but called a doctor by phone, who instructed him “on the spot”. It worked, and the child survived. Ken applied for work with the CPR in Calgary to be nearer his home, which was near Kyle, Sask. His first job was at Stephen where he and his wife Gerry established themselves.

They invited me out for supper, and I, with a new car, was eager to comply. It was there that I met Gerry’s twin sister, Jackie, who had come from Port Arthur to visit. The supper was great and before I left for Banff, I mentioned that I was going to the Stampede Parade in Calgary the next day. We had a great day. After the Stampede, we went to the grandstand. That was when Gerry got lost. We spent hours looking for her and finally went to the CPR Station, to see if she had gone home on Train 1 which left about 10 PM. It had left already, so the dispatcher wired the train at Morley to check. Sure enough, the conductor confirmed that she was aboard, bound home for Stephen. I drove Jackie home to Stephen, and we became good friends. It wasn’t long after that we became engaged. Jackie found a job in Calgary with a photograph studio as a colorist. We were married Dec. 30th in Port Arthur, Ont. That way we both beat the income tax by being able to declare married status for 1951.

Thus ends the history of my earlier life in the Bow Valley.

The year is now 1988, and Canmore is hosting a portion of the 1988 Olympics. All Nordic cross-country skiing events are to be held here. New facilities for housing athletes have been built that later will become an arena, curling rink and golf club facility; a real bonanza for the town, not to mention the on-site facilities that have been created as well.

Jackie and I were living in Medicine Hat, but our attention and hearts were looking west to Canmore. Our daughter, Ada-Jane, and her husband, Richard Veronneau, had made us grandparents four times: Patrick, in 1981, Rochelle in 1983, Sara in 1985 and Nicole in 1987. Every holiday and for any excuse, we would be up here for a visit. I had retired from the railway in late 1985 with forty years seniority, and apart from golf, was finding retirement a bit boring.

We were visiting the kids for Christmas, 1987, when Richard mentioned that the Lion’s Club was looking for people to work at the Nordic Centre during the Olympics as parking lot attendants. Jackie and I talked it over and decided that it might be fun. She mentioned it to her twin sister, Gerry, who seemed to have a similar set of mind on the matter. The result was that I parked cars at the Nordic Centre, while Jackie, Gerry and Ken were parking cars down at the lower parking lot near Quarry Lake. We stayed with Ada and Richard in their home on Three Sister’s Drive and had a great time for some two weeks. We felt we were a part of the big show.

Jackie began to dream of moving up here to be near the grandchildren. We started looking at places to buy. Real estate prices seemed shockingly high to us, compared to what we would get for our Medicine Hat home. The upshot was that we settled on a mobile unit at 203 Larch Place. Jackie said she wanted something small, so she wouldn’t have so much housework in her retirement years. Our Medicine Hat home sold promptly, and we found ourselves moving into Canmore, possession date the end of May, 1988.

We were fortunate that we were able to get memberships in the golf club that year. It was the last year for such a break, as the population began to skyrocket and memberships were restricted for many newcomers. We had been golfing here from time to time for the previous ten years, when visiting Ada and Richard. It was amazing how the golf club improved so quickly, especially with the coming of the Olympics in 1988. Before the present clubhouse was built, the Pro Shop building had been the clubhouse, and the previous Pro Shop was a small shack in front of it.

I had been retired only some two years then, and was itching for something to do. I tried driving for Canadian Mtn. Holidays, taking customers from the airport to the resort areas in B. C. between Golden and Radium in the Purcell Mountains. That wasn’t enough, so I finally got involved with Paul Kalra, who runs Petro Canada’s Canmore Service. I enjoyed the rush of business, especially in the summer months, but after a couple of years, my age began to tell, and I found I couldn’t stand for long periods. My legs complained too much. I finally retired fully about 1997.

Jackie always enjoyed swimming. Shortly after arriving in Canmore, she met Betty Arnison through the Health Unit, where we had volunteered to visit handicapped persons. While Betty was handicapped with MS, she was quite a swimmer. Jackie found she could hardly keep up with her at the pool. That is what got Jackie started swimming again.

The Canmore Seniors sports director, Vera Fawkes, was instrumental in getting Jackie interested in participating in the Provincial Senior Games. When she learned that they were to be held in Medicine Hat, Jackie began to train seriously. She brought home a Bronze medal. This was in 1992. We really enjoyed ourselves there, our old stomping grounds, where we had many friends to visit.

The next games came in 1994 at Lacombe. We stayed at a billet, and enjoyed a wonderful time with our host family. Jackie won two gold medals that year.

In 1996, the games were held at St. Paul, Alta. Jackie found that the executive had reduced the age category to one single group for age fifty-five and over. She was sixty-five, and the competition was stiff, but while she didn’t place in the medals, she was first in her age group of sixty-five and over. This qualified her to be accepted as a participant in the Canada Games to be held in Regina in September. In Regina, she won a Gold, a Silver and a Bronze in the sixty-five and over category. This was the first ever Canada games. Alberta won the largest number of medals which made them the host province for 1999.

Later, Medicine Hat was named to be the host city.

In 1998, at Three Hills, Jackie came home with a Silver and a Bronze. In 1999, the Games were at the provincial level and were held at Olds and Didsbury. This time we discovered old friends from twenty years back that we had known when living at Ralston, AB. Ian and Ruby Milligan insisted on being our host family. We had a great visit with them. Jackie, now age sixty-nine, was in the sixty-five to sixty-nine age group. She came home with a Bronze.

Each of these trips, from 1992 onward, proved to be great fun and would not have been missed for anything. Winning a medal is nice, but participating and enjoying the wonderful people we met each time was far more important to us both. Another part of my life in the Bow Valley was our association with the Canmore Seniors’ Association. Emily Kennedy was president then, and they were having trouble finding a board member to look after socials or hostesses. They wanted me to be secretary, but because of my disability in hearing everything said at a meeting, I was very reluctant to accept that post. They finally stuck me with the job of looking after the hostesses, etc. I was pretty hopeless, but the ladies were very kind, and I blundered through that year with a great deal of help from them all.

The year Jean Elliott became president, I finally found a place I felt I could contribute and became treasurer, taking over from Paul Greig. He had done a flawless job for years doing the books the old way, but I decided I could use my computer with the Quicken software which made the job much easier for me. Not only did I get the books into the computer, I was able to make a list of the members together with their birth month, mailing addresses, etc. This was of help with the Birthday Teas, because a list of each month with the phone numbers of persons having birthdays could be drawn from the computer without having to search through the entire membership each time. I also went through the itinerary of furnishings and assets, listing their purchase value and their present values after depreciation. Of course some items must be deleted when broken, sold or discarded as worn out.

I retired from the treasurer’s position after the second year with Mike Faille as president because I felt that while I had done my best, there might be others whose skills were greater and better than my own.

Old age is beginning to creep up on me. Two years ago, I began to have chest pain which resulted in my experiencing something called “Angioplasty”. It took care of the chest pain, but I had to consider a change of life style. My wife, Jackie, has been wonderful in spurring me on toward greater amounts of exercise, and less intake of food, to keep me healthy. It is a war that never seems to end. I trust it won’t end for some time as I am intending to be around for some time to come. There are far too many interesting and wonderful things going on. I just don’t want to miss anything.

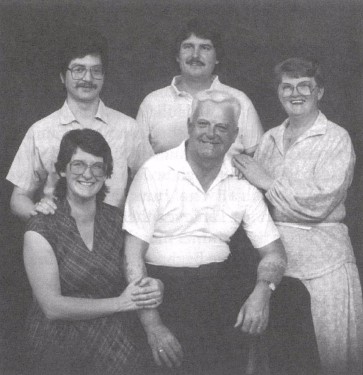

John Thomas Ferguson and Jacqueline Joan Guerard, married in Thunder Bay, Ont. Dec. 30, 1951

Ferguson family John Jr, Tom, Jackie, Ada and John Sr.

In Canmore Seniors at the Summit, ed. Canmore Seniors Association, 2000, p. 77-83