The first thing I can remember was a cold October day and there was a threshing crew in the yard. Ah, excitement. A lanky old gentleman was running, sort of hobbling, up the path to the house. I could tell he was cold as he was trying to run to warm up. I remember thinking “he is very old and will soon die.” As he entered the house, I proudly announced “Ich bin drei jahre alt” (I am three years old), my favorite expression at that time. The year was 1938 and it turns out the gentleman was thirty-four years old.

My parents emigrated from East Prussia, which was then part of Germany, in 1927. They spent three years working on a farm in Estevan, Saskatchewan until they were blown away by a tornado. As they watched their last chicken disappear in a cloud of dust, my mom exclaimed, “Mein Gott Im Himmel” They decided then and there, “we need trees”. So they loaded up a Model T with whatever they could find and headed north. They ended up hopelessly stuck in the mud somewhere near Sturgeon Lake, Alberta. There they traded the T-Bird for the highest wheeled wagon my dad could find – he was short. At that point they felt they were far enough north and filed on a homestead. And that is where I came into the picture, in a small settlement named Calais. A few years later we moved further northwest to a community called Westmark, some 50 miles north of Grande Prairie. North of Westmark was, you guessed it, Northmark, which should have been spelled NORDmark. But the story goes, the postmaster at that time, being non-German, had a habit of using the power of his authority to censor any suspicious looking letters and making any corrections deemed necessary. Hence Nordmark became Northmark. Westmark is where I began my education in a one room log schoolhouse which housed as many as 45 students; thank goodness some of them played hookey most of the time. The school was heated with wood in winter; the heater was an oil drum on its side with some legs, a door cut in the end, and a stovepipe. The older boys were usually called upon to stokeup the fire. Occasionally while one of them was accomplishing this task he would also lob a 30-30 cartridge in for good measure. This usually caused some excitement especially if the door blew off and the stovepipes fell down.

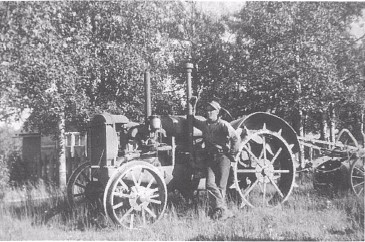

By the time I was twelve I had learned to drive a steel-wheeled, 15-30 McCormick-Deering tractor. At age fifteen I was operating a breaking outfit, and also learned the fine art of handling explosives. Dynamite was used to blast the bigger tree stumps which were too big for the breaker to handle. The blasting was generally done ahead of the breaker but some would be missed, then with the plow stuck in the stump we would set the charge, light the fuse and run around to the front of the tractor for protection, then go back and kick the debris off the platform and go until I got stuck again. One time while setting the charge, I must have pulled the detonator out of the powder, because I lit the fuse and ran for cover and waited, and waited— and nothing happened. I knew the fuse was not that long; the rule was to use a short fuse when you didn’t have far to go for cover. Why waste time, furthermore fuse cost money. There were some tense moments awaiting me as I had to back the tractor directly over the unexploded charge. Blasting was generally a two man job, my dad, being the more cautious type, punched the hole under the stump and I looked after the fireworks. This got boring after awhile so we placed his crowbar across the stump. It spun way up in the air and came down in the shape of a horseshoe – not a good plan. We did find however, that by placing a rock on top of the stump it blew the root system out more effectively, but we did have to be prepared to dodge the rock. Along with the blasting paraphernalia, a 22 calibre rifle was usually carried on the tractor for shooting prairie chickens. Since it was a single shot, extra cartridges needed to be carried in one’s pocket. Since I smoked at the time, I also carried wooden matches in the same pocket. [You’re thinking, how dumb. The other pocket had a hole in it!] One time, when the ride got particularly rough, I collided with the steering wheel. Soon after I noticed my thigh getting very warm. Suddenly I remembered the 22 cartridges. The record still stands for turning a pocket inside out.

On December 24, 1959, I married Louise Pegg whom I had met six years previously at a high school dance, but after being informed that she was only 14 I decided to put that project on hold. She was in grade ten. Louise, being the academic type, flew through school and graduated at age seventeen. Then on to University of Alberta, Edmonton. She boarded the train in Spirit River with a friend, for the ten hour “milk run” ride, with limited legal tender and instructions to find a place to live, get good marks and come home for Christmas. Others were not so lucky. Their instructions included, “Don’t talk to strangers”. They had never been south of Grande Prairie! Louise received her one year, Junior E teaching certificate, and immediately found employment in a three room school in Bonanza Alberta. Appropriately named ?? Full time teaching junior high as well as the principalship was her initiation to the profession. Because of a severe shortage of teachers in the North for a number of years, some of the students had missed one or more years of school. Not surprising then, that some of the students were nearly as old as the principal. And so began a very successful teaching career which included working full time and upgrading to a Bachelor of Education doing evening credit classes and summer school. An interesting time was also spent teaching at Tall Timbers Private School in a logging camp at Keg River, Alberta, where we were fortunate to meet Dr. Mary Percy Jackson, an interesting individual who has written several books on life in the North.

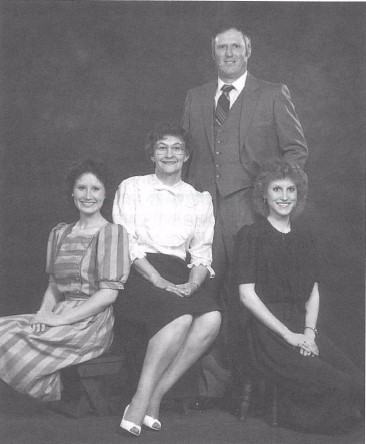

We were married on Christmas Eve, probably the only time either of us could get time off from work. We have two girls, Sandy born in May 1962, and Charlene born in January 1964. Sandy married Doug Adair and lives in Calgary. Sandy received her master’s degree in education and is currently employed by SAIT as Director of Customer Services and Registrar. Doug works as a financial analyst. Charlene is a physical therapist and currently works in a spine rehab centre in Marshfield, Wisconsin.

In the mid 60’s in an effort to enlarge the farming operation, I began driving off-highway log trucks mostly in the foothills south of Grande Prairie. At some points along the haul road one could see many miles of clear cut logging. I can remember thinking, “My god! What are we doing?” However, thanks to the efforts of Alberta Forest Service, Procter and Gamble Ltd. and Canfor to mention a few, there is a beautiful young forest growing now. This winter employment lasted eight years. After that I did some highway driving but never much liked it. We were expected to make a round trip to Edmonton, 750 miles, single driver, load and unload in one day. Ever feel nervous when you meet these guys? I also spent one summer driving for a house moving firm, a job that seldom lacked for excitement. One incident in particular comes to mind. We were in the process of moving an aluminum-cladhip-roofed barn for a customer. It was not considered a long move and highway 2A north of Grande Prairie was not a very busy route at that time. However we did have to cross a railway track. At that time all electric and telephone wires ran overhead and often followed the railroad right of way. Legally we were required to have power company crews, telephone and railway crews in attendance at such crossings. This procedure, however, was considered unnecessary in some cases and very costly for the customer. Being behind in our bookings the decision was made to “run it”. As I approached the crossing, barn in tow, I glanced up and down the uncontrolled track, visibility only a couple hundred yards to the right. As I was preparing to gun the Detroit diesel, I noticed my boss up ahead standing beside his pilot truck frantically waving his arms for me to stop. I got stopped just short of hitting numerous overhead telephone lines. Now we were in a bind. Well, they are not electric, so the boss climbed up on the roof of the barn, pulled all the wires up and slid them along the ridgecap as I slowly drove ahead. And thus the telephone system for the entire north half of the province went down for many hours to come.

By that time the farm, which we had built up considerably, required most of my spare time, even in winter. It was strictly a grain farm. When I was a kid I was required to milk a cow twice a day, [Had something to do with learning responsibility] before and after school and I wasn’t having anymore of that. Living in a forested area most of my life also taught me something about wildlife. And it is my firm belief that animals will survive in spite of us, not because of us. If this were not so, would there be coyotes in Los Angeles, deer in Calgary, bears in Grande Prairie? We grew wheat, canola, oats and fescue in that order. Fescue is a lawn seed and a high percentage of the world supply is grown in the Peace River country. Some of our “pony oats” were shipped directly to some of the US racing stables. As was advertised locally, Secretariat was fed Peace Country oats. The quality of northern grain is very high due to the climate.

There were no ski hills close by, but curling was a popular pastime, and we played it with some degree of success, as I skipped a team to the provincials four times. Coming from a small northern town however, we found the city teams somewhat tough to beat. We did however manage a third place finish.

In 1995, being tired of trying to compete with corporate farming, we decided to sell out and retire. No regrets as five years later the industry continues to slide. (Furthermore leaving the farm to your kids is now considered to be child abuse). In four hours “All Peace Auctions” sold five quarters of land, a house, household appliances, furniture, nineteen grain bins, shop equipment and a full line of farm machinery. Traumatic, perhaps, but effective. We chose Canmore as our retirement home, partly to be closer to our kids, for the mountains, clean air and water, but mostly because it’s 500 miles south. It isn’t California but it’s close.

Arnold and Louise Schulz, harvesting wheat, Peace River country

Sandy, Louise, Arnold, Charlene Schulz

Land breaking outfit in Peace River country

Logging, northern Alberta

Tall Timbers School, Keg River, AB

In Canmore Seniors at the Summit, ed. Canmore Seniors Association, 2000, p. 254-257.