Grandfather Southwood, born in Plymouth, England, in 1855, moved to Ohio and met Elizabeth Faultner from Bedford, Ohio. They married in 1879 in Cleveland, Ohio and had three children. They then moved to Montana by wagon, where Grandfather worked in the coal mines.

My father, Thomas John Southwood, was born in 1893 in Bridger, Montana. His brother, Howard, and sister, Isabell, also were born in Montana.

In 1898, they all moved back to Ohio where Ruth was born and they then trekked to Alberta, via Montana. Elizabeth, being fifteen-years-old, was made responsible for her younger siblings and would hide them in the bushes at night in case of Indian attacks in the Dakotas. At that time, there were bands of renegade Indians attacking isolated wagons that were not in a wagon train.

They arrived in Calgary in 1902 and applied for a homestead seven miles southeast of Madden. Granddad built a comfortable log cabin and made the required improvements so the family could move in.

My dad told me that Grandpa had a bad temper and was not the easiest person to live with. About 1906, he and Grandma had a quarrel and she was going back to Montana with half of everything, including three children, horses, cows, a wagon and some household furniture. A few out of Fort McLeod, an early blizzard hit them, as it was in the fall. She managed to make it to the Fort with the wagon and children but lost all the livestock in the storm. They found the cattle had smothered in the deep drifts of snow and the horses were gone.

They soon were in Montana with what was left in the wagon. Granddad wasn’t long in following them and left my dad, Howard, and Elizabeth, who were now old enough to fend for themselves.

Elizabeth (“Bessy”) married Hector MacKenzie who had a quarter section next to Granddad’s homestead. Bessy loved horses, and along with five children, raised some thoroughbreds and raced them through the summers at various meets such as Cochrane, Calgary, etc.

In 1912, she was a feature attraction at the first Calgary Stampede. She and a lady from Montana rode a relay competition all week. They would race the half-mile circuit, then change horses and race another half mile. The Montana gal won but Bessy told me how she would slash Bessy’s horse across the nose with her crop whenever it was gaining on her. Bessy got even which she said made it all worthwhile; when her opponent was just a bit ahead of her and bent over nicely, she gave her a good whack right on her backside!

In 1902, the Malloch family moved from Kansas and took a homestead about four miles south of MacKenzies’ and as their children, nine of them, ranged about the same ages as the Southwoods, they became friends and eventually of some influence on all our lives.

My Dad, Thomas, and Uncle Howard became great buddies with Don and Dave Malloch and were like the four amigos. They all bought orange angora chaps, “like leather pants,” and everybody in the neighbourhood knew where they were courting by the orange wool caught on the barbed wire gates of the various ranches.

When WW I broke out in 1914, Howard joined the army and served overseas. On his return, he married Tammie Mallock and eventually had three children, Sylvia, Gordon and Douglas.

My mother, Leila May Nelson, was born in Ohio and moved to the Airdrie area with her family in the early 1900’s. They were married in 1918 and my brother, Thomas Rex, was born in 1920, and I, in 1922. Mother passed away in 1923 and Bess MacKenzie, our Aunt, took both of us to raise with her five children, all older than us – Rose, Daisy, Donald, Edith and Margaret.

We soon called Bessy, “Mom,” and Hector, “Dad” , and went to school at Abernathy, two miles away. There were about thirty kids from around the district in grades one to eight.

These were good years, growing up. One learns many valuable things growing up on a farm ranch, being around animals and all the responsibilities that are required in raising livestock, etc. We lived in the bottom of a coulee where Nose Creek began. There was swamp as well and wildlife everywhere. At night, the frogs would chorus, thousands of them. I loved the sound. Coyotes howled in packs and night birds warbled.

In 1932, Uncle Hector passed away, leaving Bessy with seven children to raise. She was a wonderful mother and my brother and I were very fortunate to be a part of her family, as we were all treated equally by her and cared for.

I spent as much time as was allowed at the Malloch ranch with my cousin Gordon and a neighbour lad named Owen who was raised by his grandparents on a small sheep ranch two miles west of Malloch’s. The three of us spent days carving a dancing puppet, using wire to join its arms and legs. It was supported by another wire and attached to a shaft and propeller that made it dance as the wind turned the propeller. We thought it was a masterpiece and one morning, a nice chinook wind was blowing so we picked a high post in the corral and mounted our dancing man.

It was really going, legs and arms flopping, when “blam”; wood slivers flying everywhere. We stood amazed for a moment, then looked around. Grandpa Smith stood with his shotgun, grinning. Owen said, “Why did you do that, Grampa?” Grampa pointed to his windmill where the red star on the tail was full of holes. We always took a shot at it whenever we went hunting with our 22 rifles. He said, “I’ve waited a long time to get even with you boys.”

Our father became a racehorse owner and trainer and travelled the Canadian Racing Circuit all summer and often went to California and Mexico in the winter. He would come and see us when he could and would bring us something new in the way of clothing or a toy. Eventually, he started wintering his horses at Bessie’s place and built a barn, corrals, bunkhouse and drilled a well, operated by a windmill. Soon the whole family moved to this location, house and all.

Change was all around us. Roads that had been wagon trails were being graded and fenced. Cars were more common and tractors replaced teams of horses. All around us grassland was being turned into agriculture.

My brother and I soon finished our grade eight schooling; I was twelve and he fourteen. We had started school together as “Mum” thought it better for us both. Our father had remarried by then and had a daughter, Lavonne, and a son, Robert. He wanted my brother and me to have an education so we moved into Calgary with our stepmother, Myrtle, and started grade nine in Colonel Walker High School. I think I was the youngest person in that school at that time, and coming from a one-room country school, felt very uncomfortable. However, we adapted to this new lifestyle and our new family. Our father was in California racing his horses so everything was new to us in the city.

An epidemic of polio broke out in November of 1935 – there were no vaccines at that time. My brother and I soon packed our things and walked twenty-six miles to our “sister’s” farm at Big Hill Springs. We started school there as they taught up to grade twelve. This didn’t last long as the school board felt we didn’t belong in that district, so Rex went to MacKenzie’s to help out and I stayed with my sister who was expecting a child and having problems. I took over the cooking, with her instructions, and it worked out pretty well. After the baby was born, I left to work at various farms and ranches.

I spent time haying with Don Malloch and went back to the race track circuit where I spent the next three years with my father. I kept in touch with Owen and Gordy whenever possible and when I was seventeen, worked for the “White Spot” cafes as an assistant butcher. It was good training but not what I wanted to do as a lifetime trade.

In the spring of 1939, Owen and I decided to go to Banff. I soon felt this was where I wanted to live. At that time, Banff was a summer town and, after Labour Day, shut down except for local needs. My first job was fighting a forest fire at Saskatchewan River Crossing. That helped for awhile, but soon I was nearly broke and looking for something more reliable. Owen said there was a fellow looking for help at Norquay Motors washing cars. I applied and soon was a partner with Nova Warner. We were soon making good wages and learning to drive cars of all makes, delivering them to the Banff Springs Hotel and elsewhere.

War broke out in September of 1939. This was a time of big changes. More work was available as many men joined the forces for security reasons as well as patriotism, leaving jobs available. I spent that winter between Malloch’s and Bessy’s place, working for my board.

In May, I was back in Banff and worked with Nova again until my eighteenth birthday. I went to Brewster’s garage looking for a job driving for Grayline Tours. The garage was by the Banff Springs Hotel where the convention centre is today; next to the garage was Brewster’s horse corral that rented horses out for local trail rides, etc. This was run by Dick Roberts for whom I would work part-time at a later date.

Lloyd Hunter was the foreman and dispatcher for Brewster Transport. I told him I would like a job and that I could drive so he sent me out with Bert Styles. I did okay, as it were, and was given a metal badge with my number and was designated a car. Lloyd asked me my name; I said, “Just call me Ace.” This was the name Owen had introduced me as to everyone so it stuck for always. This was the start of a new and exciting lifestyle for me.

It was a great summer, driving all over the mountain parks with interesting people and working with young men from across Canada, most of them going to universities, such as Pat Costigan, Mel Butler and Bill Carter, who all became doctors in later years. Frank Hayes was our superintendent and became a friend to my father as they were both interested in the racing profession.

Soon it was the end of the season. I had saved enough money to buy a new western saddle so that fall and early winter of 1940 I rode with Don Malloch, rounding up horses in the hills west of Cochrane between the Little Red River and the Ghost River. When we had enough, we would drive them to Cochrane to be shipped east for the French Cavalry. After our work was finished, I went to Calgary and worked for Oliver’s Candy for the rest of the winter, then back to Banff.

In 1942, I worked afternoons from 5:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m., which allowed me free mornings to guide tourists on horse rides up the Spray River. I stayed with George Smith and another cowboy at the old Brewster Stables on Spray Avenue. Between driving and the horses, it kept me busy with not much time for anything else.

In May of that year, on a rainy night, I stopped at a small cafe called the “White Owl” for a snack before going off my shift. There I met the girl who would become my wife; her name was Iris Wilson. A few days later, I was driving a bus on a twilight tour and asked Iris to come along for the ride. My first stop was the town dump where bears came to forage but this evening, not a bear was in sight. The tourists (forty Americans) were disappointed, so being young and maybe not too bright, and having my girl in the bus, I said I would find them a bear. Leaving the bus, I walked into the trees on a game trail, not sure what I was going to do. At a sharp bend in the trail, I came face to face with a large brown grizzly bear! It was about fifty feet from me and coming towards me. I froze for a few seconds and thought, “Don’t panic.” So I turned and walked back the way I had come. When I was back in the clearing where the bus was parked, the bear was just behind me. I went to the bus and the bear to the dump. The tourists really thought I had found a bear and led it out for them! They didn’t know how scared I had been and I didn’t let on. I guess I wanted to impress my girl, Iris.

After a wonderful summer, too soon the season ended and, as I was twenty years old, and by then my brother was already in the army, I felt it was time for me to enlist. On September 14, 1942, I was proudly wearing the uniform to serve for the next three and a half years in the army. My basic training was at Currie Barracks, then to Camrose and Red Deer, where I took various courses while waiting to go overseas. In 1943, I was on a draft going to England, but for unknown reasons, was taken off at Debert, N.S. to serve as driver for the commanding officer of the camp. He gave me permission to get married after a few months After Iris and I were married, we had but one day before I had to return to Debert. Later she followed me and stayed and worked in Truro which was about twelve miles from camp. We enjoyed a few months together as often as I could get leave; then I was on my way to England after seeing Iris home. I had joined the forces with the Army Service Corps, hoping to be posted with my brother who was in Italy with the 8th Field Ambulance. However, I was posted to the Calgary Highlanders Regiment and served with them until the end of the war.

I returned to Canada in January, 1946, and came directly to Canmore and my wife. We bought the house we are living in at this writing and I believe it was built about 1883-84. After years of renovating, it has served as home where we raised our three children, Reginald, Terence and Lori.

I worked at Exshaw Cement Plant, Canmore Mines and other short-term jobs. In 1958, I started with Banff Park Engineering Services as a draftsman and surveyor. I had always wanted to have a guest ranch and Dead Man Flats seemed ideal. I therefore applied for a quarter section. However, I was informed that the Trans Canada Highway was being built through the area I wanted but there would be a commercial subdivision there and I could apply for land in that. I received two lots and, in 1959, built and opened a drive-in restaurant we named “Grizzly B’ar”. This was the first food outlet between Calgary and Golden, B.C.

I kept my job in Banff and Iris ran the drive-in with my help evenings and weekends. Terry and Lori both worked with us when they could, as well as several local young people. In 1962, I was appointed to the Improvement District #8 council to represent Mine Side Canmore as the Town of Canmore was divided by the river and only incorporated from the Bow River east. I served on this council for fifteen years before Mine Side was annexed by the town of Canmore. I was then on their council for another three years.

In 1967, I worked with Charles MacDonald in construction and tried to develop a ski hill on the end of Rundle Mountain, above what is now the Nordic Centre. This failed from lack of funds. I often wonder how we managed to get through those years but eventually, in 1976, we sold the “Grizzly B’ar” and I continued working at odd jobs, renovating houses, etc.

Both of our sons were married by now and pursuing their careers. Lori had a music studio at home and taught piano, drums and accordion. She also played for dances and other occasions.

Our years in Canmore were not all work and no play, as a group of us would go to the Banff Legion every Saturday night to dance to the music of Louis Trono. Some nights we went to the Canmore Legion where local bands played. We also went with Lori to the dances she played.

Then there was the golf course and the recreation centre and swimming pool we inherited from the 1988 Olympics.

I worked for a few years in the 1980’s as building inspector for I.D. #8 which is now Big Horn Municipal District.

Although many changes came to Canmore after the ’88 Olympics, nothing can destroy the beauty of our valley and mountains and Canmore will always be home to us and we’ll always have fond memories of days gone by.

THE WAR YEARS

In January, 1945, at St. Petersburg Barracks, in Ghent, Belgium, a contingent of reinforcements, having completed 6 weeks of infantry training in Aldershot, were formed up on the parade square. A tall, elderly Sergeant Major, wearing WW I ribbons, stood the parade at ease.

“Now lads”, he said, “you are going to be sent to various regiments as reinforcements up the line”! A voice muttered somewhere in the ranks, “Oh, oh, we’ve had it”! “No”, said the C.S.M., “you haven’t had it, but you’re going up to get it”. “Sparky”, my buddy through infantry training, looked at me and muttered, “This is it, I guess”! And so started our relationship with the Calgary Highland Regiment.

A day or so later, we arrived with full pack in Nijmegen, Holland, where the regiment occupied the old army barracks. A 25 pound Field Artillery piece was set up in the courtyard, firing at intervals onto some target in Germany. This was the first gun I had seen fired in anger, but certainly not the last! Within days, I would witness over a thousand guns firing for a period of four hours in a continuous barrage. This was the beginning of the Second Front, called “Blockbuster”.

We were soon digging in on a sloping area by Groesbeek. This overlooked the low lands between Holland and Germany, west of the Reichswald. Gliders used for the invasion of Arnhem were scattered over a vast area, a sad reminder of a lost battle.

Our first objective, “Wyler”, could be seen far across the low lands. A church spire stood amid trees. This was taken the following morning with few casualties as resistance was minimal due to the heavy bombardment received. Soon we were moved into a reserve position somewhere in the Reichswald and moved up slowly as the front progressed.

In late February and early March, we prepared for the push to the Hochwald. Resistance was much greater here; by the second or third day, our objective was secure and we were snug in the abandoned bunkers of the “Jerries”. Most of the following day, I watched the “Typhoons” hitting targets and chasing the new German jet planes.

Then another move to a farmstead east of the Hochwald. To pass the time, we searched for eggs and watched the boys from Support Company trying to kill a pig. Meanwhile, Sparky was given a drivers test on the T 16 personnel carrier. He did okay so was now in Support Company and was trying to get me transferred. A couple of days of respite and once more we were moving up.

We marched silently through Xanten in the early morning darkness, our way lit by the buildings still burning in the devastated city. Daylight found us grouped in a small copse of trees; this was our starting area; we could see our objective about a half mile across a stubble field, a church spire as usual in a copse of trees.

I was listening to the wireless operator, requesting mortar fire onto the objective. Through some error of coordinates, we became the target of the mortars. We were totally exposed as the missiles came screaming in. I dived into an open furrow made by a plow – it wasn’t very wide or deep but served my purpose. Mortars exploded all around, men were yelling and diving for any cover available. After about a minute, the operator finally got them stopped. When the dust cleared, only one man was wounded which was a miracle. I think it was a bad omen to start the day, though.

However, the scouts reported no sign of enemy in the area so it was a go. The sun was rising as we started forward, 180 men strung out across the field in line. I was flanked by two platoon sergeants. One remarked, “It’s too damn quiet. I have a feeling this isn’t going to be easy.” We had progressed over three-quarters of the way without incident but then, all hell broke loose – machine gun fire from front and both sides. My first impulse was to dive into the first shell hole I could find, but as everyone started running forward, so did I.

Some got as far as the edge of the trees, while I and others took refuge in old shell or bomb craters, about 50 or so yards short of the trees. I was armed with a sten gun which, in my opinion, was next to useless at any range over 50 feet. I was wishing I had my rifle. The way the dirt around the shell hole lay, I was able to see back across the area we had come from. A native from B.C., who was called “Chief” by his unit, not liking his exposure out in the field, came running in, firing his Bren gun from the hip like a cowboy but he made it!

Later, I could see someone stick a leg in the air, then both legs; this didn’t draw any fire so out he came as fast as possible, carrying two cases of antitank bombs. He made it, too.

Soon, mortars started firing on our position; being so close to their position as well, most of them landed in the field. My crater felt a bit vulnerable by its size so I began to dig a hole within it; of course, any movement detected brought machine gun fire spraying dirt over me. I had just about completed my fox hole when water started gushing into the bottom of it. Soon the water was up about half way. For the rest of the day, I was obliged to squat in it almost to my waist. So much for comfort – it was cold! Towards afternoon, other than some mortar fire and the occasional small arms outburst, things were at a “Mexican standoff”.

My neighbour in the next shell hole had been firing on several occasions, receiving return fire from a machine gun to our left; then it was quiet for a while. I could hear a gurgling cry for help from his direction so I stuck my shovel in the air and this brought instant firing. I felt helpless as I heard him call again, very weakly this time, and I knew he was hit bad. As the afternoon wore on, I was feeling the effect of the cold water and fatigue and at times must have drifted off. Then I could hear tanks rumbling and firing, not sure whether this was a counterattack or our support. Expecting the worst, I waited. Soon, out of nowhere, a Canadian soldier ran right over me – I almost shot him until I saw the uniform. I guess he thought I was dead.

I dragged myself out of my wet fox hole, legs numb, to follow this soldier into the village. Then I remembered my neighbour. He was about 30 feet from where I had been, in another shell hole. It was the sergeant I had been talking to earlier in the day. Nothing could be done for him as half his face had been shot away. He was dead. I remembered how he had told some of us in Nijmegen, this would be his last action; by rotation points he was going home and he showed us a picture of a girl in England whom he would marry in April. I cannot describe the grief I felt for this man at that moment. I hadn’t even known his name but I shall never forget him and how he died, alone in that shell hole.

I left him then and went into the hamlet. Prisoners were gathered and guarded. I was surprised at how many there were. I joined my platoon, what was left of it, and we started to dig in on a hillock covered with fruit trees. The roots made digging difficult so by the time we had a place large enough for two and hauled boards and straw for the cover, we were all in. Hot supper came then; I think it was the pig the boys from Support Company had been hanging onto at our last position. I was too tired to enjoy it and only wanted to crawl into my bunker and sleep.

I was dozing off when my bunker mate stuck his head in and told me not to get too comfortable as he had heard we had to move up again as we were not on our objective and then he left. I must have fallen sound asleep and I’m not sure what wakened me, the quiet, I think. I then heard voices and crawled out to see what was going on. They were not Highlanders and were surprised to see me there. They told me my Regiment had pulled out and they were digging in here.

Boy! – I’m in trouble now, I thought, so I got my kit, and not knowing where I would find the Regiment, went into the hamlet to find someone who would know. Someone directed me to a basement which served as Headquarters to “Le Regiment de Maisonneuve” which had relieved us with the help of two troops of tanks of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers. I asked for directions to the Calgary’s position and was advised to sit tight until daylight. I slept that night, sitting against the wall of the basement.

Next morning was clear and sunny and as I walked down a road to join my company, on the way I passed a large barn on a farmstead by the road. There was no sign of life. There were a few dead animals near the barn but still, I had a strange feeling. I shrugged it off and soon met up with my mates at their position.

I took quite a razzing from my section for coming to work so late. Lucky for me, they said; they were just about to pull out for a 10 day rest. We heard before we left that about 40 Germans had surrendered from the barn I had passed. They, too, had been waiting for daylight. I said, “Gee! If I had known, I could have done a Sergeant York and surrounded them! “

We moved out along the railroad embankment that the Sherbrooke tanks had approached on. The tracks were lying alongside or standing like a fence in places, being joined on metal ties. We marched in single file past where the tanks had knocked out a gun position. Four or five young German soldiers were sprawled where the shell explosion threw them. No one said a word; I guess by now everyone was so used to seeing such sights. I could never get used to it myself; it all seemed so futile.

Late in the afternoon, wearily we trudged on, each man putting one foot ahead of the other. Events of the last 30 days had taken a heavy toll on all. Then we heard bagpipes in the distance, growing louder, and then a lone piper came into view. Oh, what a joyful sound! As we reached him, he turned and led us on – the step picked up, heads and bodies erect, marching now, all in step to the skirl of the pipes.

I was so proud to be a part of these men and share their lot. This was when I became a Calgary Highlander in the true sense and have been proud of them to this day.

M104193 Southwood, B.M., “Ace” p.s. Both Sparky and I crossed the Rhine driving T 16 carriers for Support Company.

Iris and Ace Southwood, 1944

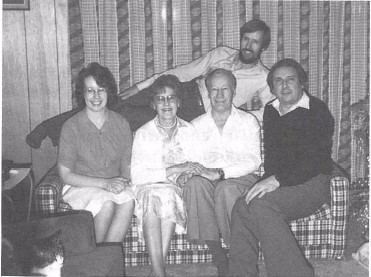

Southwood family – Lori, Iris, Ace, Reg, Terry (behind)

Ace Southwood’s parents – Leila and T.J. Southwood with Tom and Ace on wagon

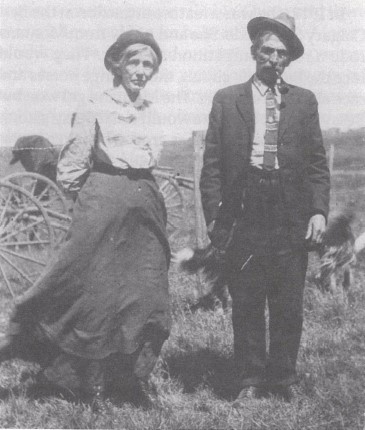

Tom and Elizabeth Southwood, Ace’s grandparents

In Canmore Seniors at the Summit, ed. Canmore Seniors Association, 2000, p. 273-280.